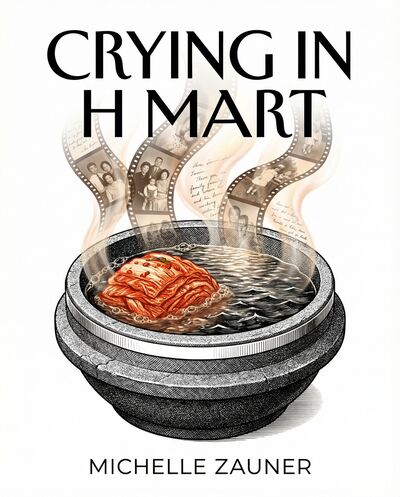

Crying in H Mart

by Michelle Zauner

When your mother is the person who taught you how to taste the world, what happens to your sense of self when she’s gone? Michelle Zauner’s story is a raw, sensory reclamation of identity through the only language left when words fail: the food that keeps us alive.

Key Ideas

In the absence of a primary cultural gatekeeper

In the absence of a primary cultural gatekeeper, the act of preparing and eating traditional foods becomes a vital mechanism for validating one's own heritage.

The book explores a 'brutal' form

The book explores a 'brutal' form of maternal love where affection is demonstrated through hyper-vigilance, strict standards, and the physical labor of nourishing others rather than verbal praise.

Terminal illness collapses the distance created

Terminal illness collapses the distance created by adolescent rebellion, forcing a shift from seeking independence to performing the duties of the 'perfect daughter' through caregiving.

Grief is likened to the process

Grief is likened to the process of making kimchi—a slow, transformative aging where something seemingly 'dead' evolves into a new, enduring, and complex form of life.

Losing a mother means losing the

Losing a mother means losing the primary witness to one's childhood, necessitating a transition where the child must become the archivist of their own history and family secrets.

Summary

Introduction

When your mother is the person who taught you how to taste the world, what happens to your sense of self when she’s gone? Michelle Zauner’s story is a raw, sensory reclamation of identity through the only language left when words fail: the food that keeps us alive.

The Grocery Store Confessional

Have you ever found yourself standing in a supermarket aisle, clutching a bottle of soy sauce, and suddenly feeling like the entire world is shattering? Imagine walking into H Mart—not just as a store, but as a sanctuary of smells and textures that hold the secret codes to your childhood. For some, it’s just a place to buy groceries. For others, it’s a site of active mourning. You see a grandmother slurping noodles in the food court, and it hits you: she’s there, and your mother isn’t.

Every bag of dried anchovies and jar of fermented paste becomes an artifact. When you’re biracial, the loss of your immigrant parent feels like losing your cultural passport. You start to panic. If there’s no one left to call and ask which brand of seaweed is the 'good' one, are you even still part of that tribe? This isn’t just about food; it’s about the terrifying realization that your link to a whole history is fraying.

The aisles of H Mart are where grief becomes physical. It’s where you realize that identity isn't just a set of ideas, but a collection of flavors you can't afford to forget. You’re not just shopping; you’re searching for a way to prove you still belong. It’s a desperate attempt to find the bridge between your American life and the parts of you that are rooted in a Seoul kitchen. Moving through these rows of produce is like walking through a museum of who you used to be.

But why does a simple bowl of soup carry so much weight? To understand that, we have to look back at how this language of love was first taught. It wasn't through hugs, but through high standards.

Gat-Kimchi and the Language of High Standards

Imagine a kind of love that doesn't say 'I love you' with words, but with a bowl of perfectly seasoned soup and a sharp critique of your posture. Most of us are used to the Western idea of soft, sentimental affection. But Korean maternal love? That’s often made of sterner stuff. It’s an industrial-strength protection that manifests as hyper-vigilance. If your mother is constantly nagging you about your skin or your grades, it’s because she is curating you to survive a harsh world.

Think of it like a master chef in a high-pressure kitchen. In Michelle’s world, being 'pretty' and being 'good' were essentially the same word—'yeppeu.' This wasn’t about vanity; it was about performance and belonging. Validation wasn’t handed out for free; it was earned on the plate. Remember being a kid and trying to impress the adults? Now imagine doing that by swallowing a piece of raw, wriggling octopus.

That culinary bravery was a shortcut to acceptance. When you eat the 'scary' traditional foods that make others flinch, you’re proving you have the right DNA. It was in the dark of night in Seoul, raiding a grandmother’s fridge for raw crab, that the bond was sealed. Your appetite becomes the proof of your heritage. If you can handle the heat and the funk, you’re one of them.

This high-standard love creates a unique pressure. You aren't just a daughter; you are a reflection of her labor. She protects you from being 'anyone’s doll' while simultaneously demanding perfection. It’s a fierce, sacrificial bond that feels like armor—until the moment you decide you want to take the armor off. That’s when the fermentation of rebellion begins.

The Fermentation of Rebellion

Do you remember that period in your life when everything your parents did felt like an embarrassment or a trap? For Michelle, growing up biracial in a mostly white town added a heavy layer of friction to that typical teenage angst. Her mother’s care felt less like a safety net and more like an anchor she needed to cut. The house was filled with the pungent scent of fermenting cabbage and the heavy weight of 'industrial-strength' expectations.

So, what do you do when you want to find your own voice? You turn to the loudest thing you can find: punk rock. Music became a way to build a world where her mother’s rules didn't apply. It was a space where she could be someone other than the 'perfect daughter.' This created a rift that felt like a canyon. At lunch, while her mother would use the steam from a hot bowl of soup to soften rice—a quiet act of care—she would simultaneously dismiss Michelle’s artistic dreams with a bluntness that stung like salt in a wound.

Every argument was a battle of wills. There’s a specific kind of stoicism in this family, captured by a haunting mantra: 'Save your tears for when your mother dies.' It’s a phrase that sounds brutal to Western ears, but it carries a generational weight of survival. It says: life is hard, so don't waste your energy on the small stuff. But when you're a teenager, that stoicism feels like coldness.

The rebellion wasn't just about music; it was about trying to scrub away the 'otherness' of her home. She wanted to assimilate, to be untethered, to live the life of a 'starving musician' because it felt authentic. But life has a way of collapsing those distances. Suddenly, the independence she fought for felt very small when the news of a terminal diagnosis arrived. How do you go back home after years of trying to escape?

The Diagnosis: Porridge and Penance

Imagine you’ve spent years trying to build a wall between yourself and your home, only to have a single phone call turn that wall into dust. When the cancer diagnosis arrived, the role of the rebel vanished, replaced by the role of the penitent. Michelle returned to her childhood home, not as a visitor, but as a caregiver. This was the shift from seeking independence to performing what’s known as 'filial piety.' It’s the idea that you owe your parents for the physical life they gave you.

But how do you pay back a debt that big? You start with porridge. Jatjuk—pine nut porridge—is a labor-intensive dish, a medicinal comfort. It was Michelle’s first real attempt at cooking for her mother, and it was a revelation of how unprepared she was. Childhood rebellion leaves you with many skills, but usually, none of them involve domestic duty or finding specific brands of Korean instant soup using broken 'Konglish.'

Caregiving becomes a ritual of penance. You find yourself scrubbing floors and lint-rolling your clothes just to meet her 'shrewd eye,' hoping that if you can be perfect enough now, it will erase the mistakes of your teens. But the reality of illness is unscripted. It’s the shock of seeing a woman who took such pride in her poise lose her hair and her agency. It’s the terrifying car rides where the person who was your rock becomes delirious and unrecognizable.

In the middle of this decline, there was a desperate scramble for joy. Why get married in a rush in the middle of a chemotherapy cycle? Because a wedding is a flag planted in the ground against the advancing dark. It was a calculated act of hope, a way to ensure the mother could witness the daughter’s future before it was too late. But as the celebration faded, the harsh silence of the sickroom returned. The daughter was still clinging to the mother, just like she did as a child, but now the roles were reversing. How do you prepare for the final transition?

The Ritual of the Witness

Have you ever wondered what it’s really like in those final moments? We see the cinematic versions of death, but the reality is far more visceral and unglamorous. It is the heavy, physical labor of tending to a body that is failing. As Michelle moved into the final phase of caregiving, the 'perfect daughter' performance fell away. There was no room for artifice when you are managing the raw cycles of survival.

You become a witness. But more than that, you become an archivist. When someone is dying, you start looking at their things differently. You see the half-finished paintings and the watercolor sets, realizing that your mother was a whole person—an artist with dreams—long before she was ever just your mother. It’s a 'strangerhood' that hits you: you are losing the person who knows you best, yet you are only just starting to truly know her.

Then comes the moment that changes everything. The act of dressing a deceased parent is a brutal, final transition. Imagine the cognitive dissonance of trying to force stiff limbs into a chosen outfit, only to have the body react in ways you didn't expect. It’s the ultimate weight of inheritance. There’s a literal passing of the ring—Michelle taking her mother’s wedding band and feeling like a fraud, like a child playing dress-up in an adult’s life.

When your mother dies, you lose the primary witness to your own history. There is no one left to confirm your memories of your toddler years or your first scrap. You are left alone with the diamond on your finger and the recipes in your head. The house feels empty of her voice but full of her things. But in those things—the jars in the pantry and the brushes in the studio—there is a blueprint for what comes next. The period of active serving is over; the period of preservation is beginning. But how do you keep a memory from rotting? You learn how to ferment it.

Fermenting Grief: The Alchemy of Kimchi

If you’ve ever felt like grief is a stagnant, heavy weight, consider the metaphor of fermentation. Making kimchi isn't just about rot; it's about controlled transformation. You take something raw, you salt it, you stress it, and then you let it sit in the dark. Over time, it doesn't die. It becomes something stronger, sharper, and more enduring. This is exactly what mourning looks like when you do it through the kitchen.

Traditional therapy might work for some, but for Michelle, intellectualizing the loss felt empty. She needed to feel the sting of the salt. She turned to digital guardians—YouTube creators like Maangchi—to teach her the 'gentle and polite' way to pull apart cabbage. This was a form of filial piety in absentia. Every time she massaged chili paste into vegetables, she was exhuring memories that had been suppressed by the trauma of the hospital room.

There is a rhythm to this labor that mends the soul. You learn the 'ambidextrous precision' required to use kitchen scissors the Korean way. You realize that your mother’s voice is actually in your hands. She once told Michelle never to fall in love with someone who doesn’t like kimchi because the smell would eventually seep through her pores. Now, Michelle was ensuring that smell was permanent.

Sublimating guilt into cooking is a slow process. It’s like the 'giving tree'—you have to figure out how much of yourself to give to the memory without losing your own future. But as the jars lined up, the grief started to change. It wasn't just a gaping hole anymore; it was a complex, living legacy. The loss was being 'salted' and preserved. You start to see that the flavors aren't just ghosts; they are the foundation. But even in the kitchen, there were still secrets to be found. Somewhere in the house, a specialized appliance held a hidden history.

The Kimchi Refrigerator's Secret

Imagine opening an appliance meant for preserving food and finding your entire childhood instead. In a Korean household, a specialized kimchi refrigerator is a staple—a temperature-controlled vault for the most important part of the meal. But after her mother’s death, Michelle discovered hers was filled with something else: hundreds and hundreds of loose family photographs. Her mother had quietly curated these, acting as a secret archivist of Michelle's life.

This is the moment the inheritance becomes clear. Her mother didn't just leave behind recipes; she left behind a record of being watched and loved. It’s a realization that forces you to shift. You can no longer be the passive subject of someone else’s care. You have to become the one who carries the culture forward.

You start to feel a desperate need to 'act' Korean. At a bathhouse, you might feel a sudden spike of anxiety that your features—the ones you share with her—are physically fading because she’s not there to mirror them back to you. You feel like you have to perform the identity to keep it from evaporating. 'If I could not be with my mother,' Michelle realized, 'I would be her.'

Preservation is an active choice. It’s finding your shoes from when you were a baby and realizing she was saving them for a grandchild she’d never meet. These objects aren't just 'high-quality junk'; they are weights that hold you to the earth. You realize that your heritage isn't something you just have; it’s something you do. You are the one who has to make the rice now. You are the one who provides the validation. The witness is gone, so you must become the witness for yourself. Here’s where the final bridge is built—not in a kitchen, but on a stage.

Chasing the Ghost of Flavor

So, how do you finally close the circle? For Michelle, the path led back to the things she once used to escape: her music and her travels. But this time, they weren't tools of rebellion; they were vessels for the legacy. She returned to Seoul, not as a tourist or a grieving daughter, but as a woman reclaiming her space. She found herself in a vinyl bar, discovering that her mother—the same woman who was so strict and pragmatic—used to perform rock songs as a child using rainboots as makeshift go-go boots.

This is the beautiful complexity of inheritance. You find the connections in the most unexpected places. Standing on a stage in Seoul, looking at her family in the crowd, Michelle finally spoke the language of the 'hoesa'—the office, the work. She was performing the life her mother cleared the path for. The success of her music felt like a posthumous gift, as if her mother was finally saying, 'Go on, then.'

When you go back to H Mart now, the pain is still there, but the purpose has shifted. You aren't just crying over the noodles. You are there because you know exactly which brand of seaweed to buy. You are there to keep the flavors alive. Connection to the dead isn't a static memory; it’s an active practice. It’s singing 'Coffee Hanjan' at a karaoke bar with an aunt who looks like a ghost of the woman you lost.

The lesson is simple but profound: food is a living history book. As long as you keep the kitchen fire burning and the jars full of fermenting cabbage, the person who taught you how to eat is never truly gone. You carry them in your palate, in the way you hold your scissors, and in the high standards you keep for yourself. You've stopped chasing the ghost and started living the legacy. The witness is still there, living through your very hands.

Read the full summary of Crying in H Mart on InShort

Open in App