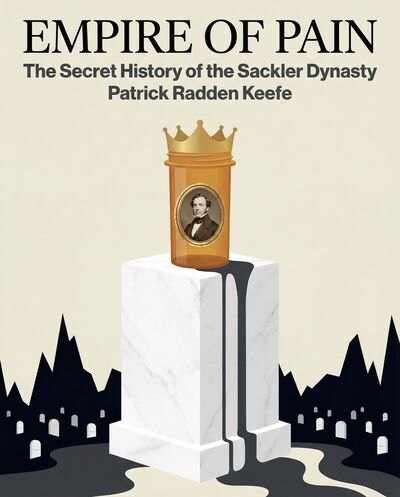

Empire of Pain

by Patrick Radden Keefe

A shocking exposé of how one wealthy family engineered America's opioid crisis through calculated deception while hiding behind charitable donations and cultural prestige.

Key Ideas

The Sacklers used massive donations to

The Sacklers used massive donations to 'transubstantiate' wealth from controversial drug sales into permanent social legitimacy by putting their name on world-class institutions.

The family successfully 'captured' the FDA

The family successfully 'captured' the FDA and other oversight bodies by employing regulators who had previously supervised them and by funding 'independent' medical movements.

Purdue Pharma weaponized thin medical evidence

Purdue Pharma weaponized thin medical evidence to claim that opioid addiction was rare, even inventing concepts like 'pseudo-addiction' to encourage higher dosages.

The Sacklers maintained a 'bunker mentality

The Sacklers maintained a 'bunker mentality,' using senior executives as human shields and bankruptcy laws as a safe harbor to preserve billions in personal wealth while the company took the legal fall.

Purdue's switch to 'abuse-deterrent' OxyContin was

Purdue's switch to 'abuse-deterrent' OxyContin was a patent-protection maneuver that unintentionally forced a captive market of users toward cheaper, deadlier street heroin.

Summary

Introduction

What if the greatest public health disaster in history wasn't an act of nature, but a carefully choreographed business plan? You're about to see how one family transformed the American landscape into a billion-dollar empire of addiction behind a veil of high-society art and elite philanthropy.

The Grand Indictment: A Crisis by Design

The Sackler family's transformation from celebrated philanthropists to architects of the opioid crisis represents a calculated business strategy, not a tragic accident. While their name adorned prestigious cultural institutions like the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the same family engineered a commercial operation that devastated communities across America, particularly in regions like Appalachia. The opioid epidemic was the inevitable result of a business model designed to maximize drug sales regardless of human cost.

The crisis stems from patriarch Arthur Sackler's realization that he could manipulate the medical establishment through sophisticated marketing. He built what amounted to a "medical-industrial complex" that transformed commercial pitches into accepted medical truths, bypassing traditional safeguards. The family didn't just sell pills—they sold an entire reality where pain elimination justified any means. This systematic approach allowed them to accumulate enormous wealth while the human toll mounted, retreating behind their fortune as communities crumbled. The story illustrates how modern capitalism's tools can be weaponized to devastating effect when profit becomes the sole driving force.

The Marketing of Addiction: Arthur's Blueprint

Arthur Sackler revolutionized pharmaceutical marketing by transforming how drugs were sold to doctors. Before him, medications were marketed through basic medical catalogs. Arthur realized he could treat doctors like consumers and sell them lifestyles rather than just chemicals, creating the foundation for modern drug advertising we see today.

Arthur built what the author calls the "Sackler Octopus"—an interconnected network of seemingly independent entities that all served his interests. This included advertising firms, medical journals, research groups, and direct-mail operations that appeared objective but were actually part of his marketing machine. His masterpiece was the Medical Tribune, a publication that looked like legitimate medical news but subtly promoted his products while keeping Arthur's involvement hidden.

The blueprint created an inescapable echo chamber for doctors, who encountered Sackler's influence in their mail, journals, and professional networks. Arthur didn't just market drugs like Valium—he marketed the concept that ordinary life stresses were medical conditions requiring pharmaceutical solutions. This approach normalized the idea of chemical fixes for everyday problems and established the marketing framework his family would later use for far more dangerous drugs.

Regulatory Capture and the FDA Sabotage

The FDA's approval of OxyContin represents a textbook case of regulatory capture, where the agency meant to protect public health instead became complicit in a pharmaceutical company's deception. Purdue Pharma exploited the "revolving door" between government and industry by working closely with FDA official Dr. Curtis Wright, who helped draft the very safety summaries he was supposed to evaluate independently. Wright then left for a lucrative industry job shortly after granting OxyContin an unprecedented safety label claiming it was less addictive than other painkillers—despite this claim being based on nothing more than a five-sentence letter to a medical journal, not rigorous scientific study.

The approval enabled Purdue's most insidious marketing strategy: the concept of "pseudo-addiction." When patients showed clear signs of addiction—craving, drug-seeking behavior, acting out—sales representatives instructed doctors that these weren't addiction symptoms but signs of "under-treated pain" requiring higher doses. This created a perfect profit cycle where the drug's failure was reframed as insufficient dosing, allowing Purdue to increase sales while deflecting responsibility. By the time the medical community recognized OxyContin as essentially high-dose morphine with a fancy coating rather than a revolutionary safe painkiller, the opioid crisis was already unstoppable, and the Sackler family had carefully shielded their personal wealth and reputation from the consequences.

The Philanthropic Shield: Reputational Laundering

The Sacklers used philanthropy as "reputational laundering" - running opioid profits through prestigious cultural institutions to transform their public image from drug dealers to cultural benefactors. They demanded their name appear prominently on every wing, gallery, and research center they funded, creating a psychological shell game where association with art museums and ancient temples would overshadow connections to pill mills and addiction.

This wasn't traditional charity but a calculated business strategy to buy social immunity. The Sacklers used tax advantages and strategic payment plans to maximize their reputational return on investment, successfully creating an untouchable public persona for decades. However, as the opioid crisis death toll mounted, institutions began removing the Sackler name, leaving "ghost marks" on walls - a perfect metaphor for a legacy defined by absence and destruction rather than contribution.

The Bunker Mentality: Profits over People

As the opioid crisis devastated communities, Richard Sackler and his family showed no remorse, instead blaming victims for abusing what he considered a "perfect" product. Internal emails revealed Sackler's contempt for addicts, whom he called "the scum of the earth." Rather than accepting responsibility, the family adopted a defensive siege mentality, using senior executives as legal shields while staying off court records themselves.

Between 2008 and 2017, as lawsuits mounted, the Sacklers systematically drained $10-13 billion from Purdue Pharma to protect their personal wealth. This strategic asset withdrawal ensured the family would remain billionaires even if the company collapsed. Their sense of entitlement was perfectly captured by Richard's dog routinely defecating in corporate offices while employees cleaned up the mess—a metaphor for the family's broader philosophy of making disasters for others to fix while believing their wealth made them untouchable.

The Heroin Pivot and the Final Betrayal

By 2010, facing patent expiration on OxyContin, the Sacklers used "evergreening" to protect their profits—reformulating the pill to make it harder to crush and convincing the FDA to ban the original version, blocking generic competition. This created a tragic irony: the millions already addicted to the original pills turned to street heroin when the new pills became expensive and difficult to abuse, effectively igniting the modern heroin and fentanyl epidemic.

Meanwhile, the Sacklers' carefully constructed philanthropic shield finally cracked when artist and OxyContin addiction survivor Nan Goldin organized dramatic protests at elite cultural institutions like the Met. These "die-ins" featuring red pill bottles and fake prescription receipts visually reclaimed spaces the family had tried to buy their way into, marking the beginning of their eviction from the cultural elite they had spent decades courting through donations.

Systemic Consequences: The Aftermath of Greed

The Sackler family exploited Purdue Pharma's Chapter 11 bankruptcy as a strategic shield rather than facing traditional criminal consequences. They offered to surrender their already-toxic company and pay several billion dollars in exchange for "global peace"—permanent legal immunity preventing any future personal lawsuits related to the opioid crisis. This effectively allowed them to purchase lifelong protection from accountability while retaining the majority of their wealth.

This outcome exposes a critical flaw in the American justice system where wealth determines consequences. While street-level drug dealers face prison for selling small amounts of heroin, the Sacklers sold billions of doses from corporate boardrooms and negotiated a settlement that preserved their fortune and freedom. The civil justice system didn't merely fail to deliver accountability—it was manipulated to protect the perpetrators, leaving the public to bear the costs of mass addiction, overdose deaths, and treatment while the family maintained their billions and gained permanent immunity from future legal action.

The Mirror of Influence: Lessons for the Future

The Sackler dynasty's rise and fall reveals how philanthropy can serve as a mask for harmful business practices. The family used charitable donations to museums, universities, and other institutions to buy credibility and influence, creating a protective shield around their reputation while profiting from the opioid crisis. This strategy of using "blood money" to purchase a "good name" allowed them to delay regulation and accountability.

Other industries—including big tech and fossil fuels—are currently employing the same playbook, using philanthropic donations to influence trusted institutions and shape public perception. When prestigious organizations accept these donations, they essentially lend their credibility to the donors, helping the public forget the problematic origins of the wealth.

The key lesson is that society must demand transparency and create clear separation between commercial profit and medical science. We need to audit the institutions we trust and ensure that reputations are earned through integrity rather than purchased through strategic giving. Without these safeguards, the next "Empire of Pain" may already be forming behind a facade of charitable respectability.

Read the full summary of Empire of Pain on InShort

Open in App